Narcan, if administered quickly and properly, can counteract the effects of an opioid overdose. Injected into the thigh’s muscle or sprayed in the nostrils, it can revive someone who is unresponsive, whose pulse and respiration seem nonexistent, whose pupils have been reduced to pinpoint size, and whose lips have turned blue or purple.

In other words, it can resuscitate someone who is just a breath away from dying.

“Every employee at The Mission who comes in contact with our clients is trained in how to administer Narcan, and always carries it with them. It is a daunting responsibility,” said Mary Gay Abbot-Young, CEO of The Mission. “I am moved beyond words every time I hear about someone on our team who responded in the moment, called out to others for back-up, then administered Narcan to someone who was dying from an overdose.” She paused, then added, “This has happened dozens of times in the past year alone at The Mission. We never know when the next time will be. It takes being constantly vigilant. And ready to respond straightaway, without hesitating.”

Dr. Eric Williams, Medical Director for The Mission, adds, “Narcan is our best and most immediate defense for someone who has overdosed. It works by blocking the effects of opiates on the brain and restoring breathing.”

He noted, “It is a daunting responsibility to administer Narcan to someone who could be dying. But our staff is very well-trained in administering it.” He added. “For those whose life is saved by having Narcan administered, the jolt is quite abrupt. So it can be quite a wake-up call. The question is: What will they do after they get that call?”

To give a glimpse into this formidable experience, here’s a story about how someone’s life was recently saved by administering Narcan at The Mission.

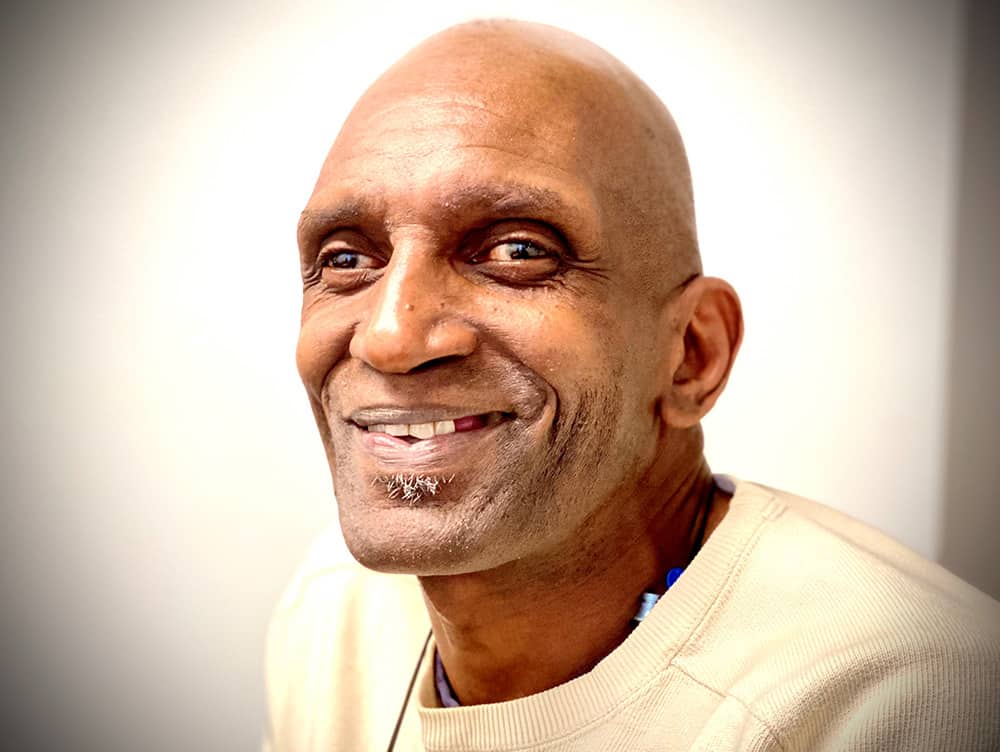

Tyrone Riley, a coordinator at The Shelter, heard a cry for help and raced up the steps to find his cousin, Lamar, unconscious and slumped over in a twisted shape on the floor. “I called on the radio for the EMT’s. Then I shook him,” Tyrone said, “but he didn’t respond. He was in a weird state. His eyes were looking up in his head. And he had turned blue.”

Tyrone – who was homeless and addicted when he came to The Shelter 15 years ago, then went through The Mission’s counseling and vocational development program for two years before joining the staff – didn’t have time to reflect on when he and Lamar were children, playing together during summers at their grandmother’s home on East State Street in Trenton.

“I shook him again,” Tyrone said. “But it didn’t occur to me to administer Narcan because, while I knew he had an alcohol problem, I’d never seen him take drugs.” Then someone called out, “I think he tried some of that bad dope on the street.”

“So I hit him with Narcan,” Tyrone said. “And he started breathing. But it was a heavy, labored breathing. Then he started gasping for air.”

That’s when Aimeé Maier, MSW, team care coordinator at The Shelter, rushed in and administered Narcan again to Lamar. He didn’t seem to be coming right out of it, so she started doing CPR on him. Moments afterwards, the EMT’s arrived to give him oxygen, stabilize him, and take him to the hospital.

When Lamar returned to The Mission the next day, he had a lot to unravel. “At first I didn’t know what happened because I couldn’t remember any of it. Then I recalled the nurse saying to me, ‘You know, you overdosed.’ And I thought, ‘I don’t think so.’ Then I realized, she had no reason to lie. And I thought, ‘why am I lying to myself?’ And I remembered that when it all happened and my eyes were shut, there was nothing there. I have a taste of that ‘gone-ness’. I was nearly gone,” he said, shaking his head. “There was nothing there. Like someone turned the switch off. Then something came back on. And I was here again.” He added, “That memory carries a lot of guilt. And I don’t want that guilt. So, this is my shot.”

Lamar asked if he could see Aimeé, who he thanked profusely for saving his life.

Later that afternoon, he met with Tyrone, who he hugged and thanked, as well. Then, together, they remembered summers when they were kids playing in their grandmother’s backyard. They talked about how Lamar played percussion in a Latin band that opened for Tito Puente in New Orleans. Then Tyrone shared a cautionary tale about a time when he was living on the streets, and he’d overdosed. “I remember looking into a white light. The next thing I knew, a doctor held his thumb and index finger a half-inch apart, and told me, ‘You came this close to dying.’ Then he said, ‘You now have a second chance.’” Tyrone paused, hoping his message was sinking in. “But I wasted it, Lamar. It took me a lot longer to find my way. I didn’t take in the seriousness of it at the time,” he said, then added “Addiction is a battle we have to fight within ourselves every day. It’s easy to slip up with this disease. Easy to let old patterns take over again. I hope you take in what just happened to you, Lamar. Don’t waste this opportunity. You were brought back to life. See it as your second chance.”

Aimeé and Tyrone now use Narcan as a verb. Between them, they have Narcaned sixteen people. “When you bring somebody back,” Aimee said, “in that moment, there is a significant crossing of two lives. Then it’s over. And who knows what will happen afterwards?”

“When you bring somebody back, in that moment, there is a significant crossing of two lives. Then it’s over. And who knows what will happen afterwards?”

What will happen afterwards to Lamar? Will he see this as his second chance, as Tyrone encouraged? Will he see today as the start of new possibilities? Or as just another day?

“While Narcan can open the door to life-changing opportunities, it doesn’t always come with a Hallmark ending,” said Barrett Young, Chief Operating Officer at The Mission.

He explained, “Most of us would understandably think that being brought back to life after an opioid overdose would have to be rock bottom, the absolute lowest point for anyone. But for those in the throes of addiction, overdosing is often far from their lowest point. And the nature of the disease, unfortunately, short-circuits their brain’s receptors. So those in the throes of addiction often cannot see their way clear to seek treatment. Instead, because the addiction is so strong and their disease has multiple symptoms – including a craving for increased levels of dopamine, accompanied by impulsiveness and impaired judgment – some individuals who are brought back from the brink return to using opiates immediately after receiving Narcan.”

“Narcan can save someone’s life,” Barrett added. “But it can’t change it. Someone whose life has just been saved has to want – make that need – to change. That’s why there’s a phrase used by many in treatment: Until you’re ready, you’re not ready. Only when someone is ready can medications in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies start to help someone on their road to recovery.”

For those who are ready, being brought back to life by Narcan can be seen as their wake-up call. They can be awe struck by the significance of the event. They can start to believe that their life must have meaning and purpose. They can see this opening as their opportunity. And being finally ready, they can take a first step in seeking treatment and committing to their own recovery.

All of this brings us back to Lamar.

Now that his life has been saved, and he has said his thank-you’s, does Lamar need to change? Does he see the significance and meaning of his life being saved? Is he ready to look inside of himself and face many daunting questions? Can he hold onto a glimmer of hope? And step into his own recovery?